| An Historical Perspective of the Salzburg Protestants |

| At the same time that the expansion of Ottoman Turks into southeastern Europe provoked great fear, cold, wet weather resulted in shorter farming seasons and food shortages causing widespread starvation. Europe was about to feel the effects of the Thirty Years War. Hunger, misery and threats of Turkish invasions aside, the archbishops continued to focus their concern on heretics, and from 1613 to 1615, the mandates against Protestants were extended by Archbishop Marcus Sittich to include the entire region. When the majority Protestant population in Radstadt demanded churches, the Archbishop increased his sternness, giving the Protestants only 14 days before exile. Out of 2,500 Protestants in Gastein, only 300 promised to live and die as Catholics. Most of Germany was destroyed beyond recognition by the ravages of the Thirty Years War as foreign soldiers burned hundreds of cities and spread destruction, death and disease, yet Salzburg was barely scathed because of the clever diplomacy of Archbishop Paris Lodron, who, even in the midst of the neighboring chaos, hosted a consecration of the newly rebuilt Salzburg Cathedral, the largest baroque building north of the Alps. The Peace Treaty of Westphalia at war's end pledged that within the German portion of the Empire, private exercise of non-conforming religion was permitted and the governments were rendered religiously neutral. Lands secularized by the Protestants in 1624 were mostly allowed to remain so, but in the Habsburg territories of Bohemia and Austria, the Holy Roman Emperor was given a nearly free hand to reimpose Catholicism, and this they did with renewed zeal. Ferdinand ll ordered the extinction of Protestantism in Austria in 1627 and once again, Lutherans were expelled on a large scale. He and his authorities set up heavily armed, guarded commissions who roamed throughout the country ferreting out offending Protestants, relying upon assistance from the well-organized and dependably loyal Jesuits who fought the Protestants by burning their books, dragging them to religious "re-education" camps, stealing their children and generally spreading terror among local populations. The relentless commissions travelled to "troublesome" Austrian parishes such as Carinthia, Styria and Lower Austria´s “Waldviertel” whose Protestants refused to conform, and by around 1652, many Protestants were forced to flee and either leave everything behind or sell their goods and property at a great loss. Some quietly slipped over the border, but often the refugees were arrested, beaten or even sent back home where they were forced to confess and take communion. Lower Austria was cleansed of Protestants by 1654. These vulnerable, early Austrian exiles wandered into new areas in small groups or alone. Approximately 100,000 Protestants, a substantial portion of the population, left Austria between 1600 and 1680, and there would soon be many more. Salzburg's Protestant salt miners bought a little more time because of their economic importance, and since the 16th century, they had grown progressively more educated as the Protestant books which had been smuggled into the region resulted in an unusually high literacy rate in small, rural Lutheran mountain hamlets. The books, which in an odd way put these simple mountain folk on an intellectual level similar to the educated German elite, were hidden away in special boxes when not in use and secreted in wood piles, hay lofts and under trap doors, safe from church spies. The books became almost sacred relics to simple farmers and miners, and were revered for use during 'Hausandacht', secret home religious services. These gatherings for friends, neighbors and even servants were usually led by the more well-versed, articulate and inspirational individuals who today might be called "lay-preachers". One such remarkable person was a humble salt miner named Joseph Schaitberger, and his name would one day be heard in all corners of the European continent and beyond. |

| More on Salzburg: |

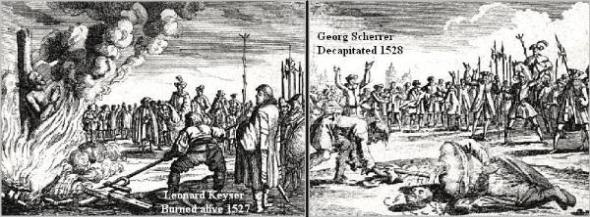

| In 1525, rioting Protestant miners and farmers joined forces with some Salzburg patricians and later with miners of Gastein in the Peasants' War, forcing Lang to flee to Hohensalzburg fortress. The peasants laid siege but failed to penetrate the fortress with their crude armor and cannons, so they decided to starve Lang out, assuming he had no ability to get food up to himself. However, legend has it that the crafty Lang outwitted them. With only one bull left in the fortress, he had the black bull paraded high up on the fortress wall within sight of the peasants, who were growing weak from hunger themselves, and then had his soldiers paint the bull white and parade it again, repeating this procedure a number of times. The peasants, thinking their tactic of starving him out was in vain, broke off their siege in December of 1525 after negotiating an agreement with Lang, who promised to address their grievances. Lang instead had a number of rebel leaders arrested and executed. By a combination of determination and deceit, Lang had outwaited and outwitted the threat. With Protestantism still spreading, Lang resorted to more violent measures which led Martin Luther to declare him a "monster". ***(In his early career Luther had been an admirer of Konrad Muth, the leader of the Mutianischer Bund and the Kabbalistic secret society, Obscurorum virorum ("Obscure Men"). In 1514 Luther justified Judaism's resistance to Christendom, believing that only his reformed religion would prove attractive to multitudes of Jewish converts. (Cf. G. Lloyd Jones, On the Art of the Kabbalah [Lincoln, NE: Univ. of Nebraska, 1993], pp. 23-24). When the anticipated mass conversions failed to take place, the embittered reformer penned, "On the Jews and their Lies," [Luther's Works, Philadelphia: Fortress, 1971, v. 47]. This infamous, 1543 advocacy of arson and vandalism had no Scriptural warrant and has been rightly condemned. However, scant attention has been paid to Luther's 1525 pamphlet, Against the Robbing and Murderous Hordes of Peasants, in which he advised the rulers to "stab, strike and strangle" the "Satanic" German peasants. Luther's homicidal polemic against the peasantry was written in the same year that saw the slaughter of more than 6,000 peasant rebels in Thuringia, a pogrom that is seldom the focus of any outrage or commemoration. Luther's polemic against Jews was mild in comparison.). Sadly, through deception, all Protestants were either were imprisoned, expelled and burned alive, and Lang had Pastor Georg Scherer decapitated and his body burned in 1528 as a warning to other would-be heretics. Lang and his successors remained steadfast Catholics from then on, enjoying absolute rule. Even Lang's harsh measures were not enough to stifle the desire for freedom among some of his people, however. It took another two centuries to fully eliminate the Protestants from Salzburg. |

| Long ago, there was a beautiful land nestled in snow capped mountains in a far away corner of the world where ancient people found safety and a pleasant existence with plentiful game, abundant fish in the clear rivers and streams, verdant forests to provide heat in winter and flowers and herbs to keep them healthy. They cleared pastures, built homes, raised animals and crops, and most importantly, discovered a treasure deep within the earth to harvest and trade for that which they lacked. Hundreds of years before the birth of Christ, these ancient miners recognized the necessity and value of salt. The development of Salzburg into a powerful Archbishopric goes back to the Romans who occupied and developed the land south of the Danube, turning the area into a province of the territory of Noricum. Although Christianity was introduced to the area early, the religion vanished under barbarians until the 8th century when Charlemagne burst upon the world stage and imposed Christianity throughout Europe. He can be credited for marking the boundaries and ensuring the territorial sovereignty of the Archbishopric of Salzburg, and when Archbishop Hartwik's church was consecrated in Salzburg in 996, Salzburg became a thriving, independent city-state. Awkwardly sandwiched between Austrian lands and neighboring Bavaria, Salzburg was ruled by the powerful archbishops. The responsibility to elect the archbishop and sustain his authority rested upon a chapter of twenty four canons drawn from the nobility, and they put the administration of Salzburg and its lands entirely in the hands of the archbishop who regulated every aspect of life, from business and legal administration to education and the military. Emblematic of this temporal power was the Fortress Höhensalzburg, built by Archbishop Gebhard in 1077 and successively improved by successive Archbishops. It is the largest fortification in Europe, and throughout its long history has never been captured, occupied or successfully besieged by its enemies. The Salzburg archbishops opened salt works around Hallein in 1200AD and grew rich by buying up shares in the mines until they held them all by the 16th century. Massive revenue, ten percent of the world's gold along with a vast share of salt, poured in from the mines and Prince Archbishop Leonhard von Keutschach, who ruled from 1495 to 1519, elevated Höhensalzburg from a purely military fortress into a structure representative of power and pomp. One of the most enigmatic personalities in the long series of bishops, von Keutschach invested huge amounts of money into decoration, modernization and extensions as he transformed the dreary fort into a pleasant castle. Throughout the structure, his coat of arms with its white turnip on a black field is emblazoned on marble plates. Fifty eight turnips later, Von Keutschach had an organ built in 1502 which made horn-like sounds that communicated with the townsfolk in a method akin to the use of alpine horns in the valleys, and the “castle horn” woke the people up at four in the morning and signaled their bedtime at seven each night. It also reminded everyone of the Archbishop's power over them. He was the last feudal-style ruler of the city. He reformed the city finances, paid off old debts and developed the Salzburg economy, turning it into one of the richest lands of the Holy Roman Empire, with his coinage reform used as the basis for Salzburg's modern monetary system. He repurchased lands sold by his predecessors, expanded the city's defenses by strengthening the fortress and a number of other castles in the area, ordered the construction of river dams in Hallein to prevent destructive spring flooding and built roads to further promote the salt trade. |

| "It is not the cure, but the physician who prescribes it that I dislike," said the Archbishop of Salzburg, who had been peculiarly bitter against the Reformers. "I would oblige the laity with the cup, and priests with wives, and all with a little more liberty as regards meats. Nor am I opposed to some reformation of the mass; but that it should be a monk, a poor Augustine, who presumes to reform us all, is what I cannot get over." Spoken of Luther in 1530 at the Diet of Worms |

| SALZBURG PROTESTANT EXILES |

| Salzburg History |

| Archbishop Matthäus Lang von Wellenburg (ruled 1519-1540), was the son of an Augsburg burgher and he assumed the name of Wellenburg from a family castle. After his education, he entered the service of emperor Friedrich III and became one of the most trusted advisers of Friedrich's son and successor Maximilian I., with his loyalty rewarded by several promotions within the church hierarchy. Pope Julius II made him a cardinal, and in 1514 he became coadjutor to the Archbishop of Salzburg, whom he succeeded in 1519. Arrogant and ambitious, Lang was unpopular among the people of Salzburg. He recruited Saxon miners, who in turn brought in Protestant ideas. Realizing the danger too late, he was determined to keep the populace Catholic by any means. While at first he tolerated a bit of criticism aimed at the church, when poet/scientist Paul Speratus openly spread Luther´s word in Salzburg, Lang had him expelled. When Karl V was elected Holy Roman Emperor in 1519, Lang prodded him to take punitive measures against Martin Luther. Below: Luther and Lang |

| In 1504, when von Keutschach expanded Höhensalzburg, heavy building materials had to be transported up the mountain. There was already a rudimentary rope and pulley system with wooden tracks, first described in a 1411 book as a "funicular" which transported goods up to the fortress. Von Keutschach improved this, making it the oldest mountain railway still in operation in the world. The old hand-operated system was inspired by the operation of mining cars and worked by prisoners ("penitents") who laboriously turned a capstan. It took tremendous strength and a long time to pull the hemp ropes by hand for the train to make its steep journey, and sometimes the rope broke. The funicular is shown in the print on the left. |

| Dietrich and his woman, left. Dietrich scratched on his prison wall the words: "Lieb ist Laydes Anfangkh über kurz oder lang" (Love is the beginning of suffering, sooner or later). Salome had also been arrested, but was released soon after and moved to Upper Austria where her children could flourish. She wore black the rest of her life and was never allowed to see her love again after his arrest. Salome Alt died on June 27, 1663 at age 95. |

| Meanwhile, new trade routes brought a period of economic and social change to Europe. By 1575, the wealthy Archbishops were so preoccupied buying luxury goods once reserved for the wealthiest of kings, that many of them were oblivious to the fast growing Protestantism. While the church hierarchy fiddled with silks, rugs and precious gems, nearly all aristocrats and three fourth of Salzburg's citizens had become Lutheran! Rome was not happy, and at a Munich Conference in 1579, Catholic delegates of Inner Austria, Bavaria, Tirol and Salzburg quietly met and planned how to battle the Protestant threat. Stomping out heretics old-style had simply not been effective. Aristocratic Archbishop Wolf Dieterich von Raitenau (1559-1617) was prepared for religious life from childhood and was elected Archbishop of Salzburg in 1587 at the young age of 28. He sought advise in Rome and issued a proclamation upon his return for all Protestants to recant or leave within a month, with permission to sell their goods and property first. So many chose exile that he revised the mandate so as to confiscate their property. By 1588, the openly Protestant population of Salzburg was expelled and the city was left with 7,000 citizens, all of them Catholics or pretend Catholics. Many Salzburg Protestants migrated into other German speaking areas around 1600 and founded such towns such as Freudenstadt in the Black Forest. Various peasants and salt miners again took up arms in defense of their Lutheran faith in 1601, but this revolt was also crushed. A zealous absolutist, strict reformer and counter-reformationist, Dietrich amassed great art collections and hired Venetian master Vincenzo Scamozzi to develop plans for a magnificent Baroque renewal of Salzburg. While he demanded obedience from his subjects and strict adherence to Catholic dogma, he could not lead by example: this Archbishop was in love! Salome Alt (1568-1663), the daughter of a wealthy merchant, was described as one of the most beautiful girls in Salzburg, with chestnut hair and grey eyes. Dietrich established Lock Altenau (now Mirabell) for his love, with a hidden door connecting their bedrooms. He furnished the palace grandly and landscaped it well. For 22 years they were faithful to each other, and Salome bore him a total of 15 children. Alas, the Archbishopric came hopelessly into conflict with Maximilian of Bavaria, and in October of 1611, Dietrich ordered 1,000 Salzburg troops to occupy Berchtesgaden. Maximilian responded by sending 24,000 men into Salzburg, forcing Dietrich to flee the city. Maximilian had the Archbishop arrested, and on November 23, 1611, Dietrich was sent to gloomy, 11th century Hohenwerfen fortress where he was imprisoned and formally deposed. Four years later, Dietrich died in Hohenwerfen in agony, possibly from poisoning. |